Losing a parent is something like driving through a plate-glass window

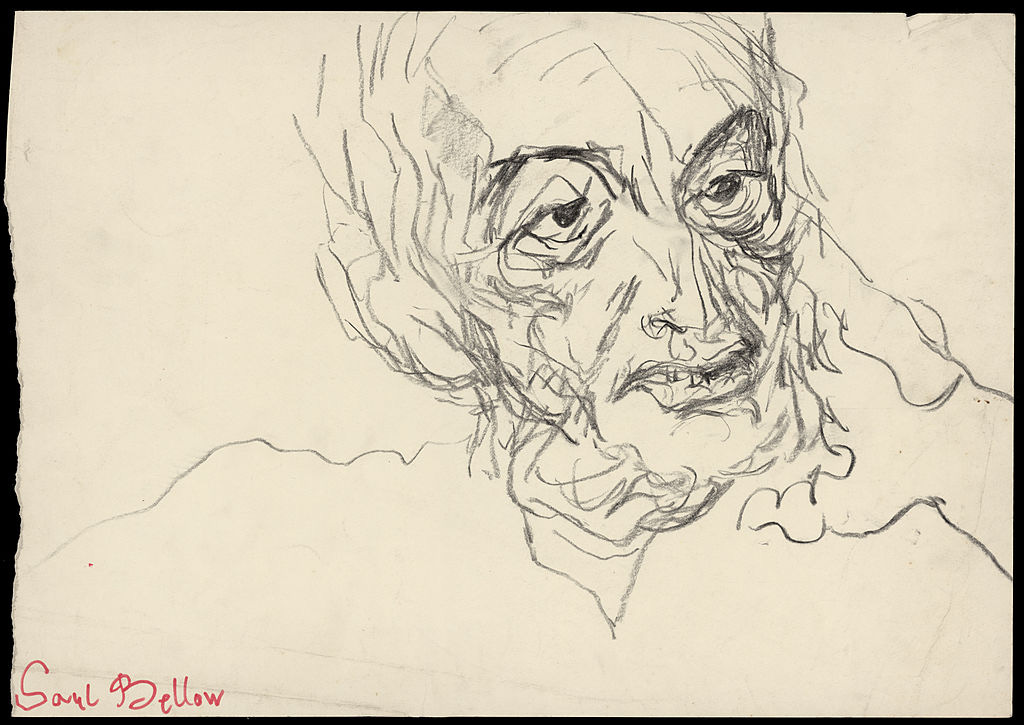

Saul Bellow writes to Martin Amis

The following letter can also be found in the book, Letters of Note: Fathers.

Novelist Martin Amis had a difficult relationship with his father, Kingsley, a fellow author and poet, who was vocal in his distaste for his son’s work. In 1983, Martin was sent by the New York Observer to interview his idol, Saul Bellow, whom he considered to be the greatest American writer of all time, and a friendship blossomed. Twelve years later, after Kingsley suffered a debilitating stroke and died, Martin reportedly called Bellow and said, ‘You’ll have to be my father now,’ to which Bellow is said to have replied, ‘Well, I love you very much.’ This letter was written the next year. Bellow makes reference to his bout of ciguatera fish poisoning in 1994, from which he nearly died, an experience he fictionalised in his final novel, Ravelstein.

March 13, 1996

Brookline, Mass.

My dear Martin:

I see that I’ve become a really bad correspondent. It’s not that I don’t think of you. You come into my thoughts often. But when you do it appears to me that I owe you a particularly grand letter. And so you end in the “warehouse of good intentions”:

“Can’t do it now.”

“Then put it on hold.”This is one’s strategy for coping with old age, and with death—because one can’t die with so many obligations in storage. Our clever species, so fertile and resourceful in denying its weaknesses.

I entered the hospital in ’94, a man biologically in his forties. Coming out in ’95, I was the Ancient Mariner, and the Mariner didn’t write novels. He had only one story and delivered it orally. But (I told myself) you are a writer still, and perhaps you’d better come to terms with the Ancient.

I may be about to resolve all these difficulties, but for two years they have totally absorbed me.

I’ve become forgetful, too. Nothing like your father’s nominal aphasia. I find I can’t remember the names of people I don’t care for—in some ways a pleasant disability. I further discover that I would remember people’s names because it relieved me from any need to think about them. Their names were enough. Like telling heads.

I can guess how your father must have felt at his typewriter, with a book to finish. My solution is to turn to shorter, finishable things. I have managed to do a few of those. Like learning to walk again—but what if what one wants, really, is to run?

I am sure you have thought these things in watching your father’s torments.

Last Saturday I attended a memorial service for Eleanor Clark, the widow of R. P. Warren. I found myself saying to her daughter Rosanna that losing a parent is something like driving through a plate-glass window. You didn’t know it was there until it shattered, and then for years to come you’re picking up the pieces—down to the last glassy splinter.

Of course you are your father, and he is you. I have often felt this about my own father, whom I half expect to see when I die. But I believe I do know how your father must have felt, sitting at his typewriter with an unfinished novel. Just as I understand your saying that you are your dad. With a fair degree of accuracy I can see this in my own father. He and I never seemed to be in rapport: Our basic assumptions were very different. But that now looks superficial. I treat my sons much as he treated me: out of breath with impatience, and then a long inhalation of affection.

I willingly take up the slack as a sort of adoptive father. I do have paternal feelings towards you. It’s not only language that unites us, or “style.” We share more remote but also more important premises.

And I’m not actually at the last gasp. I expect to be around for a while (not a prediction but an expectation). “Whilst this machine is to me,” Hamlet told Ophelia.

Yours, with love.

Letter originally reprinted in Saul Bellow: Letters by Saul Bellow, edited by Benjamin Taylor, copyright © 2010 by Janis Bellow. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. / Copyright © 2010, The Estate of Saul Bellow, used by permission of The Wylie Agency (UK) Limited.

Absolutely marvellous. This is exactly how it is.

I love being the fly on the wall in these relationships. Very illuminating.